The incorporation of double extortion is a turning point in the ongoing evolution of ransomware. Modern ransomware attacks follow the same modus operandi: Encrypt the targeted organizations’ files and demand payment in exchange for access restoration. However, since there is no guarantee that cybercriminals will keep their word, some organizations opt not to pay ransom, especially if they keep backup files anyway.

But in late 2019, Maze pioneered the double extortion technique with a demand that was harder to ignore: Pay up, or the ransomware operators would publicly release the victims’ data.

To date, we have spotted 35 ransomware families that have employed double extortion — and the list just keeps growing. It’s not difficult to see why: While loss of access to files alone already puts heavy pressure on affected organizations to yield to ransom demands, the added threat of public exposure further tightens the noose, especially if classified information is on the line.

| AgeLocker | CryLock | Hades | NetWalker | REvil/Sodinokibi |

| Ako/MedusaLocker | DarkSide | LockBit | Pay2Key | Ryuk |

| AlumniLocker | DoppelPaymer | Maze | ProLock | Sekhmet |

| Avaddon | Egregor | Mespinoza/Pysa | RagnarLocker | Snatch |

| Babuk Locker | Ekans | MountLocker/AstroLocker | Ragnarok | SunCrypt |

| Clop | Everest | Nefilim | RansomExx | Thanos |

| Conti | Exx/Defray777 | Nemty | RanzyLocker/ ThunderX | Xinof |

Table 1. The ransomware families we spotted employing double extortion from November 2019 to March 2021Source: Trend Micro™ Smart Protection Network™ infrastructure

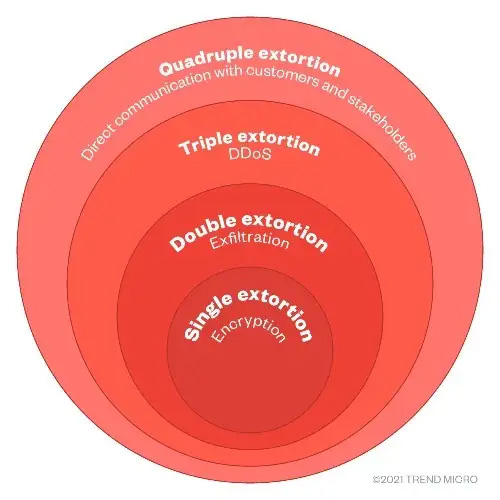

As if such a scheme isn’t bad enough, ransomware operators are now adding multilevel extortion techniques such as launching distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and/or hounding customers and stakeholders of victim organizations.

In this article, we analyze extortion techniques used with ransomware beyond encryption, lending a preview of how this threat will continue to mutate. We examine three major ransomware families that employ these schemes: REvil (aka Sodinokibi), Clop, and Conti. We handpicked these three since they are currently active, feature new techniques, target big companies, and perform different levels of extortion. Notably, all three also operate under a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) scheme, which means that they are propagated more easily and more quickly through affiliates. The three are also reportedly the successors of notorious ransomware families.

The phases of ransomware extortion

Before delving into the attack phases of the campaigns involving the three ransomware families under consideration, it’s only fitting to examine how ransomware extortion has developed over time. Here are the phases of ransomware extortion as seen in various campaigns.

Single extortion

Single extortion involves deploying the ransomware, which then encrypts and bars access to files. The operators then demand payment from the affected organization in exchange for decrypting the files. This had been the case even in the early days of ransomware.

Double extortion

With double extortion, malicious actors go beyond just encryption by also exfiltrating (sometimes through weaponized legitimate tools) and threatening to publicize an affected organization’s data. These ransomware operators usually have dedicated data leak sites, but they can also release the stolen information in underground forums and blog sites.

Maze was the first ransomware family associated with this. Its so-called successor, the 2020 newcomer Egregor, also makes use of this technique, as discussed in our annual cybersecurity roundup report. Members of the Egregor ransomware cartel were recently arrested with the help of private-public sector partnerships, including Trend Micro.

DarkSide, another ransomware family that emerged in 2020, also used double extortion techniques in a recent high-profile attack on Colonial Pipeline, a major fuel supplier in the US.

What makes double extortion tricky to deal with is that even when a victim company could restore all lost data, the threat of having sensitive information publicized remains. This was the case with a video game development company that was able to restore its data from backup but still had to struggle with the theft of source codes and other sensitive information, which were later released on a site associated with Babuk Locker.

Triple extortion

Triple extortion follows a straightforward formula: adding DDoS attacks to the aforementioned encryption and data exposure threats. These attacks could overwhelm a server or a network with traffic, which in turn could halt and further disrupt operations.

This was first performed by SunCrypt and RagnarLocker operators in the latter half of 2020. Avaddon soon followed suit. Malicious actors behind REvil are also looking into including DDoS attacks in their extortion strategy.

Quadruple extortion

All the preceding phases mainly affect only the targets. With quadruple extortion, ransomware operators reach out directly to a victim’s customers and stakeholders, thereby adding more pressure to the victim.

DarkSide operators employ the quadruple extortion scheme in some of their attacks by launching DDoS attacks and directly contacting customers through designated call centers.

Recently, malicious actors behind Clop emailed customers, informing them that their private information would be published on a website, and urged them to contact the affected company. REvil operators also recently announced that they would be reaching out not just to a victim’s customers but also to business partners and the media through voice-scrambled VoIP calls.

Different ransomware families use different levels of extortion; some implement only the first phase, while others are dabbling in fourth-phase strategies. Also, these levels are not always performed in order, as in the case of Clop, which went straight from double extortion to quadruple extortion.

Having defined the phases, we now home in on the three ransomware families in question: REvil, Clop, and Conti. Their activities are summarized here based on several attacks that have been observed and documented in our own monitoring and in external research.

REvil

First known as the alleged successor of the notorious GandCrab, REvil has since stepped out of its predecessor’s shadow, having adopted more advanced techniques such as double extortion. The ransomware’s use of double extortion continues to this day, issuing exorbitant million-dollar demands to organizations that have fallen prey to its operators’ campaigns. REvil was recently used in a ransomware attack on JBS, the largest meat processor in the world.

Extortion scheme

For double extortion, REvil has a dedicated data leak site, but its operators also post data on underground forums and blog sites. The ransomware’s operators seem determined to go all out with extortion: Besides considering DDoS and directly contacting customers, business partners, and the media, they are now also auctioning off stolen data.

Attack chain and tactics

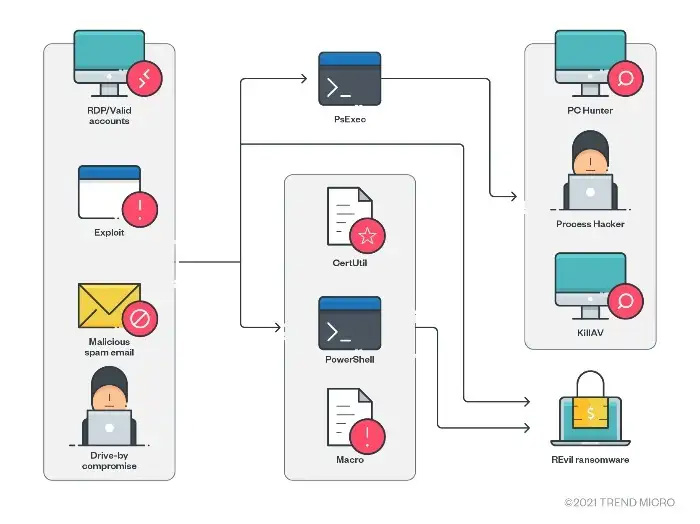

The following figure shows a typical REvil attack chain.

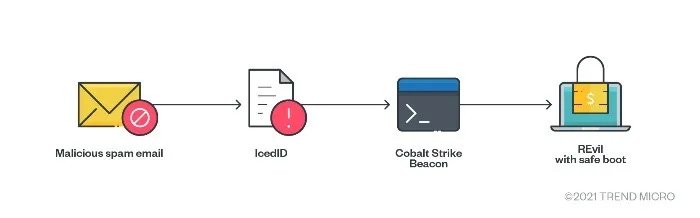

Recent variants of the ransomware also use the IcedID banking trojan, which is known for campaigns that steal real email conversations and repurpose them for malicious spam. This then leads to the downloading of Cobalt Strike Beacon for various purposes and, eventually, REvil. Safe boot then forces the system to reboot into safe mode before encryption.

Initial access

REvil has various means for initial access, including:

- Malicious spam emails with spear-phishing links or attachments

- Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) access or valid accounts

- Compromised websites

- Vulnerability exploits

In more targeted approaches, REvil can also be spread using RDP and PsExec to take control of the network and then deploy the payload.

Download and execution

REvil can be downloaded and executed in the system through:

- Macros from malicious spam emails

- Drive-by compromise, which directly leads to the downloading of REvil

- Loading in PowerShell memory via reflective loading instead of executing a binary

- Exploiting CVE-2019-2725, which leads to the remote code execution of Certutil/PowerShell for downloading and executing REvil

- Exploiting CVE-2018-13379, CVE-2019-11510, and valid accounts, which leads to the abuse of RDP and PsExec, and then the dropping of tools that disable antimalware, exfiltration tools, and, finally, REvil.

- Executing IcedID (from malicious spam), which leads to the downloading of Cobalt Strike Beacon to deploy REvil. (This is seen in recent variants.)

Lateral movement, discovery, and defense evasion

- In more targeted attacks, operators can use RDP and PsExec for lateral movement and for dropping and executing other components and the ransomware itself.

- Operators can abuse the legitimate tools PC Hunter and Process Hacker to disable antimalware solutions by discovering and terminating associated services or processes.

- Operators can also use the custom binary KillAV, which is designed to uninstall antimalware solutions.

Command and control

- REvil sends a report, which includes system information, to its command-and-control (C&C) server.

Exfiltration

- REvil drops various exfiltration tools.

Impact

After execution, REvil can perform several steps, including:

- Attempting to escalate its privilege via CVE-2018-8453, or token impersonation and creating a mutex

- Decrypting its JSON configuration file to identify elements that will dictate how it will proceed with its routines, such as which processes to terminate, which C&C server to report to, and which extension to use

- Proceeding with its encryption routine

Clop

Clop (sometimes stylized as “Cl0p”) was first known as a variant of the CryptoMix ransomware family. It got on the double extortion bandwagon in 2020, when Clop operators publicized the data of a pharmaceutical company. Since then, the ransomware’s extortion strategies have become progressively devastating.

Extortion scheme

Operators pressure a targeted organization by sending out emails to initiate negotiations. If these messages are ignored, they will threaten to publicize and auction off stolen data on the data leak site “Cl0p^_-Leaks”. Beyond this, Clop ransomware operators also wield other extortion techniques, such as going after top executives and customers.

Attack chain and tactics

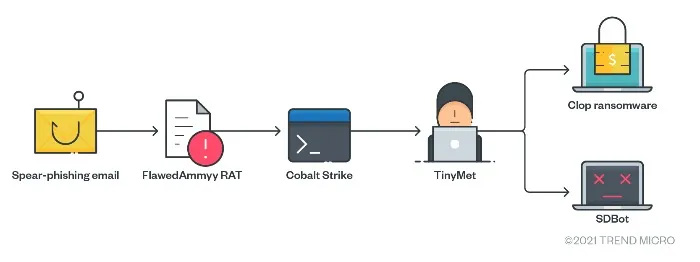

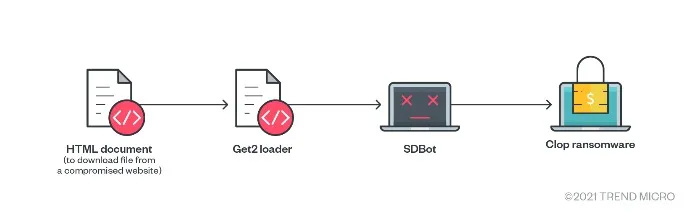

Clop has changed tactics numerous times. Upon the ransomware’s emergence, the threat actor group TA505 used spear-phishing emails in delivering Clop. These were sent to as many employees as possible to increase the chances of infection.

Around a year later, TA505 used SDBot as its only tool for collecting and exfiltrating data.

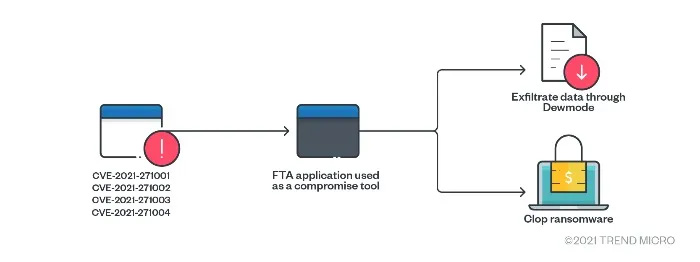

Recently, a threat actor group exploited four zero-day vulnerabilities found in a legacy file transfer appliance (FTA) product as the point of entry for its attacks.

Initial access

Clop can enter a system through any of the following methods:

- Spear-phishing emails sent to employees of the target organization

- Using compromised RDP for brute-force attacks

- Exploiting certain known vulnerabilities

- Exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities in an FTA product (CVE-2021-27101, CVE-2021-27102, CVE-2021-27103, and CVE-2021-27104)

Download and discovery

Clop can use several tools to collect information, including:

- The FlawedAmmyy remote access trojan (RAT), which gathers information and attempts to communicate with the C&C server to download additional malware components

- Cobalt Strike (Cobeacon), which is downloaded as an additional hacking tool

- The SDBot RAT, which is used to study the network, load additional malware, and deactivate security solutions to prepare for the deployment of Clop

- Compromised FTA product

Command and control

- TinyMet can be used to connect the reverse shell to the C&C server.

Exfiltration

- In one attack, Dewmode was used to exfiltrate stolen data.

Impact

- The ransomware payload terminates various services and processes, and then proceeds with its encryption routine.

Conti

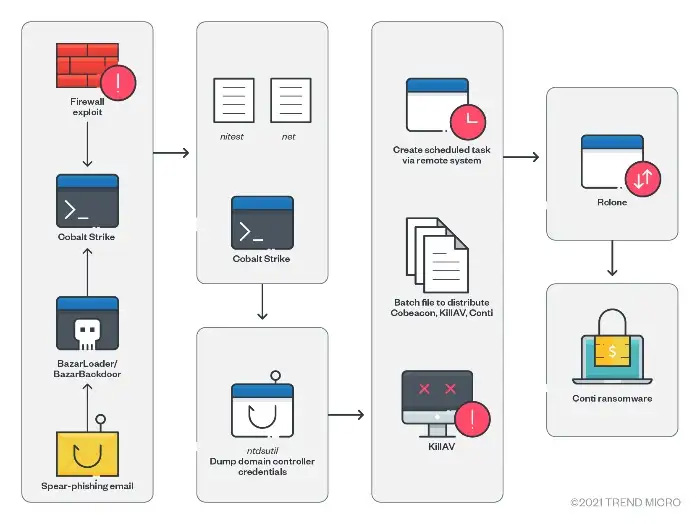

The Conti ransomware, which was recently used in an attack on Ireland’s Department of Health, also employs double extortion schemes. In some attacks, the ransomware has been distributed via the same methods used to propagate Ryuk, such as the use of Trickbot, Emotet, and BazarLoader. In an attack in February, operators also exploited vulnerabilities of a firewall product. We recently showed how Trend Micro Vision One™ was used to track Conti.

Extortion scheme

Conti employs double extortion schemes. Operators publicize data stolen from nonpaying victims on their designated data leak site. There are no confirmed reports yet of triple or quadruple extortion schemes involving Conti, but given how swiftly operators adopt different techniques, it’s not impossible for these to be incorporated into Conti campaigns as well.

Attack chain and tactics

The following shows a Conti attack chain based on several campaigns.

Initial access

Conti operators can use either of the following to gain initial access:

- A spear-phishing email that leads to BazarLoader (aka BazarBackdoor) and Cobalt Strike

- The firewall vulnerabilities CVE-2018-13379 and CVE-2018-13374, followed by the use of Cobalt Strike to gain a foothold in the system

Network discovery and credential access

- Operators can perform network discovery tactics to locate targeted assets. Cobalt Strike is also employed for this purpose.

- Operators also gain access to the system by performing credential dumping. In our research, we identified potential credential dumping attempts that used ntdsutil to dump ntds.dit, a database that stores Active Directory data. This data can be used to gain password hashes offline.

Lateral movement and defense evasion

- After obtaining the necessary credentials and access, operators can perform lateral movement by remotely creating scheduled tasks of the payload. The payload can include Cobalt Strike, KillAV scripts, and Conti. Operators also remotely execute these using scheduled tasks and batch files.

- To evade detection, operators use KillAV, which disables security software.

Exfiltration

- After identifying the target systems and gaining access to them, operators use the cloud storage synchronization tool Rclone to upload files to the Mega cloud storage service.

Impact

- Operators deploy the ransomware and encrypt files. Distribution and execution of the ransomware are done via the creation and execution of scheduled tasks on remote systems.

How to prevent ransomware attacks

Ransomware may be rapidly evolving in terms of the different extortion techniques used by operators, but the threat is not altogether unstoppable. To protect systems, organizations can follow security frameworks, such as those set by the Center of Internet Security and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Adhering to these frameworks can provide benefits such as reducing risk levels and exposure to threats and vulnerabilities. Organizations can conserve time and effort in planning as the frameworks’ specific and established practices show how and where to start and which measures to prioritize. These frameworks also boost resilience against attacks, since they involve repeatable and flexible measures that can help with prevention, mitigation, and recovery.

Here are some of the best practices from these frameworks:

Audit and inventory

- Take an inventory of assets and data.

- Identify authorized and unauthorized devices and software.

- Audit logs of events and incidents.

Configure and monitor

- Deliberately manage hardware and software configurations.

- Only grant admin privileges and access when absolutely necessary to an employee’s role.

- Monitor the use of network ports, protocols, and services.

- Implement security configurations on network infrastructure devices such as firewalls and routers.

- Have a software allow list to prevent malicious applications from being executed.

Patch and update

- Perform regular vulnerability assessments.

- Conduct patching or virtual patching for operating systems and applications.

- Update software and applications to their latest versions.

Protect and recover

- Enforce data protection, backup, and recovery measures.

- Implement multifactor authentication.

Secure and defend

- Perform sandbox analysis to examine and block malicious emails.

- Employ the latest version of security solutions to all layers of the system, including email, endpoint, web, and network.

- Spot early signs of an attack such as the presence of suspicious tools in the system.

- Enable advanced detection technologies such as those powered with AI and machine learning.

Train and test

- Perform security skills assessment and training regularly.

- Conduct red-team exercises and penetration tests.

Organizations would benefit from security solutions that encompass the system’s multiple layers (endpoint, email, web, and network) not simply for detecting malicious components, but for closely monitoring suspicious behavior in the network.

Trend Micro Vision One™ provides multilayered protection and behavior detection, spotting questionable behavior that might otherwise seem benign when viewed from only a single layer. This allows detecting and blocking ransomware early on before it can do any real damage to the system.

With techniques such as virtual patching and machine learning, Trend Micro Cloud One™ Workload Security protects systems against both known and unknown threats that exploit vulnerabilities. It also takes advantage of the latest in global threat intelligence to provide up-to-date, real-time protection.

Ransomware often gets into the system through phishing emails. Trend Micro™ Deep Discovery™ Email Inspector employs custom sandboxing and advanced analysis techniques to effectively block ransomware before it gets into the system.

For an even closer inspection of endpoints, Trend Micro Apex One™ offers next-level automated threat detection and response against advanced concerns such as fileless threats and ransomware.

Indicators of compromise

REvil

| SHA-256 | Trend Micro pattern detection | Note |

| f4f73a451c1ec493eb3b4395d06de73598fcf5b8f7d13e81418238824d90fda3 | Ransom.Win32.SODINOKIBI.SMTH | Variant with safe boot |

| 939f58c10211a768f664a8f54310dcc42eb672887be61d5d377b5a88be107b9d | Ransom.Win32.SODINOKIBI.THB | Variant without safe boot |

| 55f041bf4e78e9bfa6d4ee68be40e496ce3a1353e1ca4306598589e19802522c | PUA.Win32.PCHunter.A | |

| bd2c2cf0631d881ed382817afcce2b093f4e412ffb170a719e2762f250abfea4 | PUA.Win64.ProHack.AC | |

| ade80ac4cc963d28d44b2f63a732d72b101c82803cbf6aea178449c9bf1b58fa | Trojan.BAT.KILLAV.BI |

Clop

| SHA-256 | Trend Micro pattern detection |

| e8d98621b4cb45e027785d89770b25be0c323df553274238810872164187a45f | Ransom.Win32.CLOP.NV |

| eba8a0fe7b3724c4332fa126ef27daeca32e1dc9265c8bc5ae015b439744e989 | Ransom.Win32.CLOP.I |

| af1d155a0b36c14626b2bf9394c1b460d198c9dd96eb57fac06d38e36b805460 | Backdoor.Win32.FLAWEDAMMY.AB |

| 5202e97f1f5080de9e043378717cbaf271a3c5b3e5b568e62a8aa3150f3e1ca8 | HackTool.Win32.TinyMet.K |

| 84259a3c6fd62a61f010f972db97eee69a724020af39d53c9ed1e9ecefc4b6b6 | Trojan.Win32.WUSUB.A |

| 99c76d377e1e37f04f749034f2c2a6f33cb785adee76ac44edb4156b5cbbaa9a | Backdoor.Win32.SDBBOT.AA.tmsr |

| 23df383633ba693437d92dbcf98fca62c52697f446913e4f7f81e29dad9e26a0 | Trojan.X97M.GETLOADR.THIAOBO |

| 5fa2b9546770241da7305356d6427847598288290866837626f621d794692c1b 2e0df09fa37eabcae645302d9865913b818ee0993199a6d904728f3093ff48c7 | Backdoor.PHP.DEWMODE.A |

Conti

| SHA-256 | Trend Micro pattern detection |

| 25ef51bb1ec946cce673fbf465f693cea3095e12bccd19a157751913d18946ab | Backdoor.Win32.COBEACON.THCOCBA |

| f022d977dd0977052a8590d69982ee8e44f1ca61b01060d235c89c61f466f211 | Trojan.PS1.KILLAV.AA |

| 3c8fc04c1b3c4a9242c2dff03bce0deae7a1fbf8d1735ea7af41c5762b288f14 | Ransom.Win32.CONTI.J |

| 243408d1fa0c8a7a778d8bb224532c649409d0db76fc0ca2be385d193da22b1e | Trojan.PS1.BAZALOADER.YXAK-A |

| 5381da3db80e524b982cbc9edb795bbe5524c27311a1c36d08d2784a88fa46c5 | Trojan.BAT.RUNNER.AVP |

| a6bb0087b4321af82f6737ba7a87ca96cf59a54427a97e4eed4800bd5426e7f7 | HackTool.BAT.KillAV.AA |

MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques

REvil

| Initial access | Execution | Privilege escalation | Defense evasion | Discovery | Lateral movement | Collection | Exfiltration | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1078 – Valid accounts | T1059 – Command and scripting interpreter | T1134.001 – Access token manipulation: token impersonation/theft | T1562 – Impair defenses | T1082 – System information discovery | T1563 – Remote service session hijacking | T1560 – Archive collected data | T1041 – Exfiltration over C&C channel | T1486 – Data encrypted for impact |

| T1190 – Exploit public-facing application | T1203 – Exploitation for client execution | T1068 – Exploitation for privilege escalation | T1480 – Execution guardrails | T1057 – Process discovery | T1570 – Lateral tool transfer | T1490 – Inhibit system recovery | ||

| T1566 – Phishing | T1140 – Deobfuscate/Decode files or information | T1012 – Query registry | T1489 – Service stop | |||||

| T1189 – Drive-by compromise | T1083 – File and directory discovery |

Clop

| Initial access | Execution | Privilege escalation | Persistence | Discovery | Defense evasion | Lateral movement | Command and control | Exfiltration | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1566 – Phishing | T1106 – Native API | T1068 – Exploitation for privilege escalation | T1543.003 – Create or modify system process: Windows service | T1082 – System information discovery | T1562 – Impair defenses | T1021 – Remote services: SMB/Windows admin shares | T1071.001 – Application layer protocol: web protocols | T1041 – Exfiltration over C&C channel | T1486 – Data encrypted for impact |

| T1078 – Valid accounts | T1083 – File and directory discovery | T1202 – Indirect command execution | T1490 – Inhibit system recovery | ||||||

| T1190 – Exploit public-facing application | T1057 – Process discovery | ||||||||

| T1018 – Remote system discovery |

Conti

| Initial access | Execution | Persistence | Privilege escalation | Discovery | Credential access |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1566 – Phishing | T1106 – Execution through API | T1053.005 – Scheduled task/job: scheduled task | T1078.002 – Valid accounts: domain accounts | T1046 – Network service scanning | T1003 – OS credential dumping |

| T1190 – Exploit public-facing application | T1059.003 – Command and scripting interpreter: Windows command shell | T1165 – Startup item | T1083 – File and directory discovery | T1555 – Credentials from password stores | |

| T1047 – Windows Management Instrumentation | T1547.004 – Boot or logon autostart execution: Winlogon Helper DLL | T1018 – Remote system discovery | T1552 – Unsecured credentials | ||

| T1204 – User execution | T1057 – Process discovery | ||||

| T1053.005 – Scheduled task/job: scheduled task | T1016 – System network configuration discovery | ||||

| T1069.002 – Permission groups discovery: domain groups | |||||

| T1124 – System time discovery | |||||

| T1082 – System information discovery | |||||

| T1033 – System owner/user discovery | |||||

| T1012 – Query registry | |||||

| T1063 – Security software discovery |

| Lateral movement | Defense evasion | Command and control | Exfiltration | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1570 – Lateral tool transfer | T1562.001 – Impair defenses: disable or modify tools | T1095 – Non-application layer protocol | T1567.002 – Exfiltration over web service: exfiltration to cloud storage | T1486 – Data encrypted for impact |

| T1021.002 – Remote services: SMB/Windows admin shares | T1140 – Deobfuscate/Decode files or information | T1105 – Remote file copy | T1490 – Inhibit system recovery | |

| T1055 – Process injection | ||||

| T1055.012 – Process injection: process hollowing |

Authors/Co-authors: Janus Agcaoili (AVAR 2021 Virtual Speaker), Miguel Ang, Earle Earnshaw, Byron Gelera, and Nikko Tamaña

Company: Trend Micro

Comments are closed.